Veterans home | WWL TV | Mike Perlstein | May 12, 2020

“NEW ORLEANS — Berlin Hebert Jr. was a renegade, a bearded and tattooed loner. He loved his motorcycles, especially three-wheelers, despite losing a leg in Vietnam.

“Someone nearby him stepped on a land mine and he had shrapnel in both of his legs,” said his son Neal Hebert.

Ras Eugene Deakles was super outgoing, a deeply religious family man who served in the Army as an infantryman, chaplain’s assistant and recruiter.

“He talked to everybody he met,” said his daughter, Valerie Deakles. “He loved life. He loved to sing, he loved to fish, he loved the Boston Red Sox, that was his big thing.”

“But he loved the Lord most of all,” his wife, Sue Deakles added.

They were an odd couple, Ras and Berlin, but they became roommates and pals at the Southeastern Louisiana Veterans Home in Reserve in St. John the Baptist Parish. Their families bonded.

“My daughters grew up there,” Willman said.

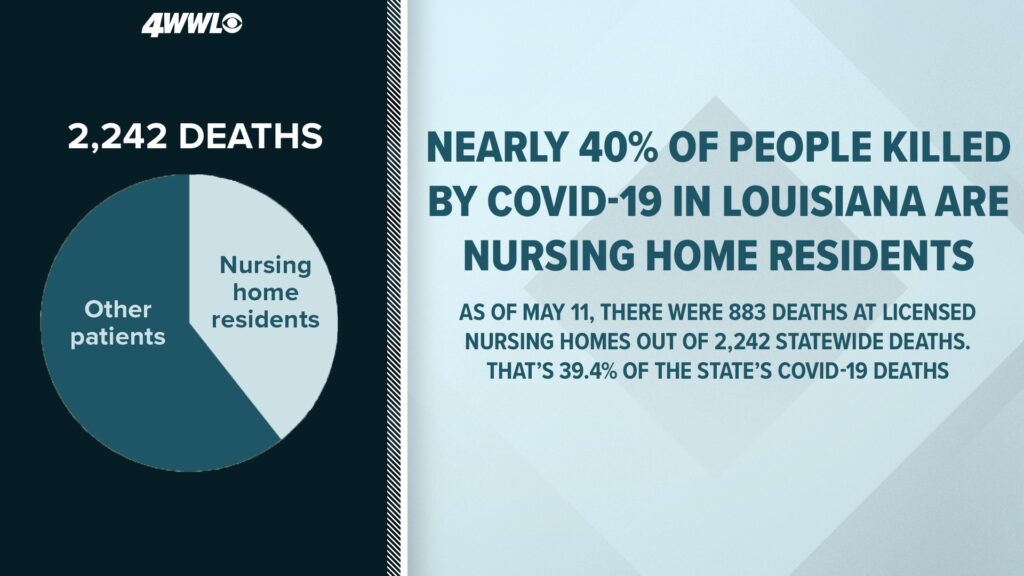

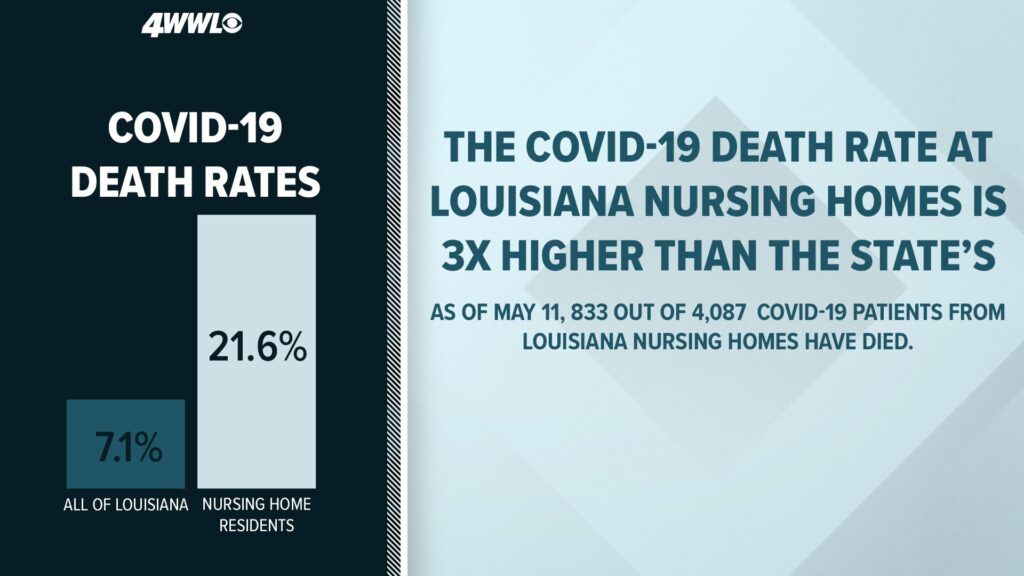

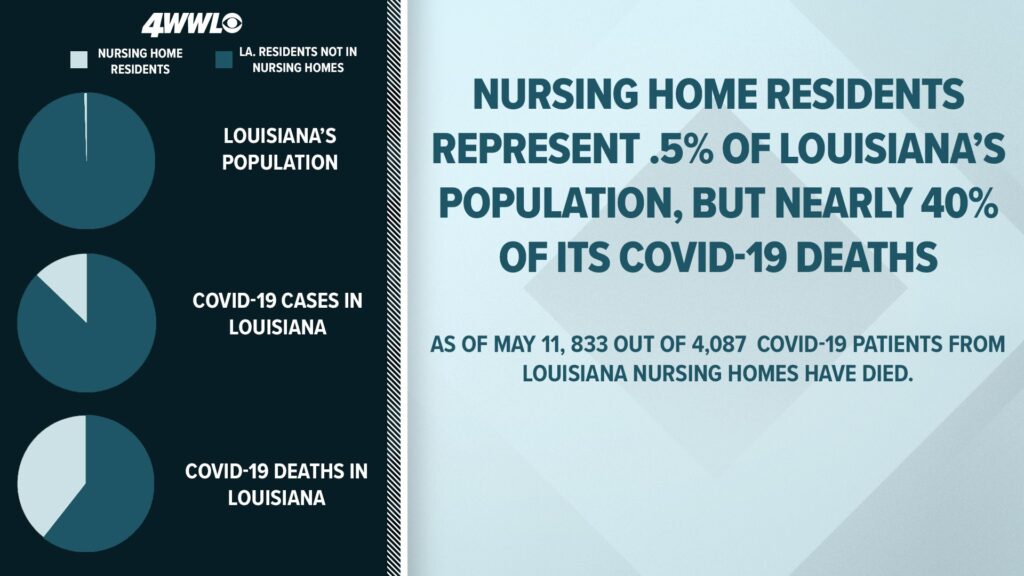

Then the coronavirus hit Louisiana. It started like a sneak attack, but quickly turned into an all-out assault. Residents at hundreds of nursing homes became sitting ducks, none more than at the veterans home in Reserve.

“Once a couple of cases get started there in a facility like that, it’s just hard to contain it,” said Dr. Christy Montegut, St. John Parish coroner.

The Deakles were bringing Ras’s young granddaughters to see him in mid-March when they got the bad news: All visitation was suspended.

“My 3-year-old, that broke her heart. That really broke her heart not being able to see her papa,” Willman said.

Within days of the state-ordered shutdown, families of the 144 residents were getting phone calls about a rising infection rate.

Hebert grew concerned about his father.

“I asked the obvious question: I said, ‘Well, is there any reason to believe my father’s been exposed?’ And I was told no,” he said.

Most of those phone calls were made by veteran’s affairs employees, many from other state veterans homes with no COVID-19 cases, reading from a script.

But on March 25, Neal Hebert got a different kind of call.

“I’m calling about your father,” said the voice on the other line.

“He had extremely high temperature, he was coughing, he had a dry cough,” Hebert recalled. “I said, ‘I thought he wasn’t exposed.’”

Berlin Hebert spent six days in a hospital, then was sent back to the home for hospice care. He died there on April 3.

Thanks to a nurse, Neal got one last chance to talk to his dad.

“The nurse started crying as well. And my dad tried to talk back, but he was too far gone.”

Hebert said the nurse gave no hint that the virus was spreading rapidly there, an outbreak that would ultimately claim at least 28 of the veterans and infect 52 more.

But Neal sensed something ominous in the nurse’s voice.

“This was not the first time that this nurse had to do what she was doing,” he said. “And I found that very alarming.”

The combination of so many sick and elderly residents in such close quarters was no match for the deadly and highly infectious virus. Experts say memory problems, such as Alzheimer’s, can make the situation worse, with some residents unable to understand and follow safety procedures such as social distancing.

“That’s so hard. I think that’s on an individual basis. Because I think some people may be able to take on that information, but for others it’s too much,” said Jennifer Reeder, a social worker with Alzheimer’s Foundation of America.

“It is like a perfect storm,” Dr. Montegut said.

The Deakles family heard that Ras’ roommate was sick, but they had no idea it was from COVID-19, much less that he had died. They got a Facetime call with Ras on April 4.

“He was sitting there eating his ice cream. He was fine. He just couldn’t wait until he could see us again,” Willman said.

Three hours later, his daughter got another call. Ras was gone.

“All I could do was scream,” she said. “Because I didn’t think it was true. It couldn’t be true.”

What the family did not know was that Ras Deakles had been given hydroxychloroquine, an anti-malaria medication now being tested as a therapy for the coronavirus. Even though Deakles held power of attorney to make all medical decisions for her husband, she said she was not notified.

“They even have to call me if he’s getting a flu shot, if it’s OK to give him the shot,” she said. “Something this major and they didn’t even call me to get permission?”

The drug has been controversial, first touted by President Trump prior to rigorous scientific testing, then found to cause more harm than good in an observational study at VA hospitals. Clinical trials are now showing the drug may be useful in mild COVID-19 cases, but it is being discouraged in patients who are very sick or have underlying health issues, as Ras did.

“That’s my first thought,” Deakles said. “It was the medicine. Because he was fine.”

Julie Baxter Payer, the state’s deputy secretary of Veteran’s Affairs, said the drug was administered to 22 residents at Southeastern before it was abruptly stopped amid the controversy.

“It was used completely in compliance with the way the FDA put out its guidance,” Baxter Payer said. “After some questions were made about the VA use, the federal VA use of it, our physician no longer prescribed hydroxychloroquine.”

Baxter Payer said all five of the state’s veterans nursing homes are following strict protection protocols, including social distancing, protective equipment and strict isolation from outside visitors.

The homes in Jackson, Jennings and Bossier have had no COVID-19 cases. At the home in Monroe, there have been seven positives cases and no deaths.

“We put into place the protocols and the lockdowns,” she said.

So, what happened at Southeastern? Families question how rigorously the home followed the protective measures.

Photographs from the home’s Facebook page show residents and staff in common areas not wearing masks. An entire series of shots show the residents holding signs to communicate messages with their cut-off loved ones.

“Some of those pictures even the workers are right up to the residents,” Willman said “They didn’t have gloves on. They didn’t have masks on. Nothing.”

Baxter Payer said she couldn’t confirm when those photos were taken, but she acknowledged that 22 employees tested positive for the virus. She gave the staff credit for persevering amid death and their own personal danger.

“As the death toll began to mount, it was very, very hard on our staff,” she said. “All 28 of those veterans mattered to our administrators, to our nurses. I’ve been on the phone with many of them in tears. We mourn every one of those 28 veterans.”

But the families had little idea of what was going on inside the nursing home. The usual ceremonial send-offs, the community outpouring, the typical military funerals couldn’t happen. Families relied on each other to find out who was sick and who died.

Hebert said his mind is filled with unanswered questions.

“What did they do differently? What was going on there that caused the virus to go rampant? That’s what I keep asking myself,” he said. “There’s a very likely chance if my dad had gone to a different veterans home he’d still be alive.”

The Deakles family tried to contact the nursing home with their questions. They are still waiting for a response.

“We tried to call the home. Nobody will call us back,” Willman said.

With the very sudden death of Ras Deakles, his family is left with distinct memories of that final video call. They thought there would more.

“My girls threw kisses,” Willman said. “And we just said I love you.”

“I had no idea it would be the last time,” Deakles said.

Unlikely friends in life, COVID-19 victims hours apart, Berlin Hebert and Ras Deakles remained opposites even in death.

Hebert wanted no trace of the military at his funeral. Deakles was set for a full gun salute. Instead, at a funeral limited to 10 family members, they got a stripped-down honor guard and a bugler playing taps.

The full honors ceremony will have to wait.”

FREE Consultation | 504-523-2434

Peiffer Wolf handles Nursing Home and Residential Care Abuse and Neglect cases throughout the country. You deserve to have an attorney that understands the process, the litigation, and the seriousness of these issues affecting your life. If you believe that you or your family have a Nursing Home Neglect or Nursing Home Abuse claim, please contact Peiffer Wolf today for a FREE Consultation.